EAT UP on You Bet Your Garden… again!

Rooftop greens at Uncommon Ground || photo by Lauren Mandel

As a self-proclaimed Class 1 NPR geek I live for public radio. You can imagine my excitement when gardening celebrity Mike McGrath interviewed me on his nationally syndicated radio show, You Bet Your Garden, this past September. As it turns out, appearing as a guest on public radio – with producers, sound engineers and fancy microphones – is even more thrilling than listening to it. What’s even better is when your interview airs again!

That’s right! Tune into this week’s You Bet Your Garden to hear my interview with Mike as part of a “Best Of” compilation. The show will air at varying times and days of the week on 50 public radio stations throughout the U.S., so to hear the broadcast live be sure to check You Bet Your Garden’s website. You can also listen to the show on Sirius/XM Satellite Radio ‘NPR Now’ Channel (#122) on Saturday and Sunday morning at 7:00 am EST. In Philadelphia (where You Bet Your Garden is taped) the show will air at 11:00 am EST on WHYY (90.9-FM).

hot tamale

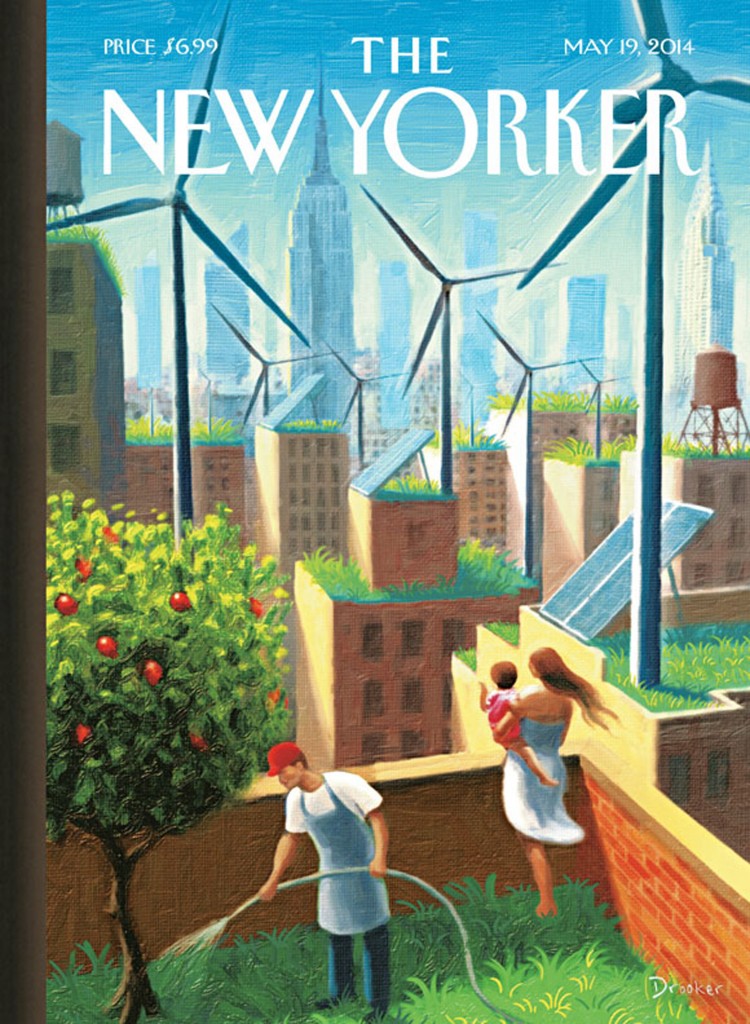

Since The New Yorker’s first publication in 1925 the magazine’s cover has served as a visual sounding board for New York culture. This month’s issue will make any rooftop agricultural enthusiast beam with pride as artist Eric Drooger depicts the Big Apple’s skyline bathed in green roofs, wind mills and fruit trees.

“I painted a future that’s completely achievable,” Drooker told New Yorker Culture Desk writers, “A Bright Future.” And he’s right. New York City already leads the country in commercial rooftop acreage thanks to pioneer farming companies like Eagle Street Rooftop Farm, Brooklyn Grange and Gotham Greens. The vision of hyper-local rooftop produce is also within reach for some school children and families from Manhattan to the Bronx. It’s happening, and The New Yorker knows it.

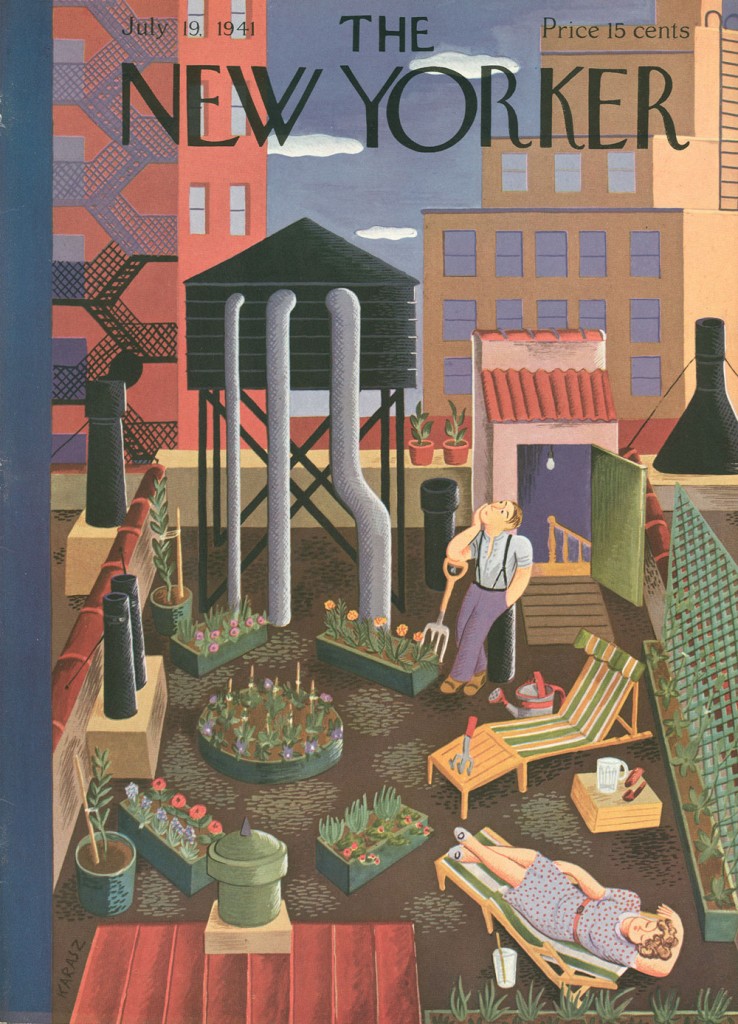

Interestingly this is not the first time rooftop agriculture has graced the magazine’s cover. Last July, less than a year ago, the cover art by Ivan Brunetti featured raised vegetable beds, herb pots and fruit trees atop a New York City roof.

In fact, since 1937 The New Yorker cover has celebrated rooftops at least thirteen times, three times prominently portraying food production. With a variety of styles and visual splendor, here are the highlights. Bon appétit!

an onion blooms in the desert

Gaza refugees planting a rooftop pilot project || photo by Refutrees

Amid conflict and persistent food insecurity Palestinian refugees are cultivating their rooftops to produce fresh vegetables close to home. Last week the Middle Eastern sustainability news website Green Prophet reported that families in West Bank refugee camps are growing subsistence crops and sprouts of hope with the help of international organizations and local non-profits.

Aida Refugee Camp volunteers || photo by Refutrees

One such non-profit, Refutrees, launched a rooftop gardening pilot project in January within Gaza’s Aida Refugee Camp in partnership with local cultural organization Lajee Center. The community-built raised bed garden, born from five-years of urban agricultural research conducted by the partner organizations, reflects a collective effort to improve food access and community health to Gaza’s 44% food insecure population. Volunteers and local youth planted the rooftop garden – which is protected by a plastic high tunnel – with lettuces, radishes and onions. The organization hopes that the pilot project will demonstrate the potential of rooftop gardening thereby encouraging 20 families to build rooftop gardens across the camp and ultimately beyond.

Many West Bank refugee camps lack space for agriculture and other essential activities that traditionally occupy the landscape. Cultivating the little space that is available within the volatile camps may present serious concern for personal safety, thereby placing the refugees in a precarious situation when it comes to food production. “Rooftop gardens in refugee communities [can] provide access to fresh, organic produce, create safe educational spaces, and… develop capacity for sustainable livelihoods,” states Refutrees’ website. Furthermore, rooftop gardens pose a practical solution in that they take advantage of flat roofs, a staple of Middle Eastern building stock. Many Middle Eastern cultures already view flat rooftops as an accessible part of the house, so gardening in this space is a natural step forward for many.

Bethlehem refugee rooftop garden || photo by Karama Organization

Fourty-five miles east of Gaza, 15 families in Bethlehem’s Dheishah Refugee Camp similarly began gardening their rooftops, in 2012, thanks to assistance from the Karama Organization. The local NGO, whose name translates to “dignity,” promotes women’s education through its Rooftop Micro-Farming Program. By providing water tanks, soil, seed, planter materials and training, the group empowers women within the camp to grow fresh produce for their families and neighbors. Tomatoes, eggplant, green beans, cucumbers, strawberries and other vegetables previously inaccessible to most refugees are now a part of daily life for some.

Political and religious views aside, rooftop gardening in refugee camps has gained international attention by addressing food security while cultivating hope. “It gives me a connection to the land,” Rooftop Micro-Farming Program participant Hajar Hamdan told Karama Organization in 2012. “My family were farmers and I’ve come back to my roots. It gives me the feeling I’m sitting in a big field. This is my big field.”

open source seeding

Tomato seedlings at SHARE Food Program || photo by Lauren Mandel

Earlier this week a group of scientists and food activists launched a campaign to change how seeds are governed. Headed by University of Wisconsin vegetable breeder Irwin Goldman and sociologist Jack Kloppenburg, the Open Source Seed Initiative released 29 new crop varieties that are free for public use under the organization’s open source pledge.

If you’re viewing this post through Mozilla Firefox you’re taking advantage of “open source software,” software that’s created collaboratively for public use, modification, and sharing. Believe it or not, seeds used to work like this too. Farmers would breed crops for specific characteristics (like sweet fruit or rapid growth), collect the seeds, then share those seeds with other farmers. Each generation of seeds could be freely bred for new characteristics, therein diversifying the gene pool.

Within the past 20 years, this seed exchange has become jeopardized as farming giants and biotech companies such as Monsanto and Dupont Pioneer turned seed breeding into big business. Seeds developed by these companies are patented. Planting seeds collected from patented crops not only violates intellectual property rights, but may yield seedlings that differ from the original crop if the mother plants were hybrids. This culture of privatized genes means that large corporations control our access to crop varieties while restricting farmers’ ability to collect and breed plants freely.

The open source seeds released this week include new varieties of broccoli, kale and quinoa, among other crops. “These vegetables are part of our common cultural heritage,” Professor Goldman told University of Wisconsin-Madison News, “and our goal is to make sure these seeds remain in the public domain for people to use in the future.”

The Open Source Seed initiative is a critical step in reclaiming equitable access to our food system’s gene pool. Open source seeds will soon be available online through the organization’s website and heritage seed companies such as High Mowing Organic Seeds and Wild Garden Seed. Want to learn more? Listen to NPR’s April 18th coverage on open source seeding:

no water? no problem.

Self-watering planters in late-afternoon light || photo by Lauren Mandel

All this talk about high-tech rooftop farming makes my hungry for a good old fashioned DIY project. Presenting: the self watering planter.

As you may recall from an earlier post, “the naked truth,” my Philadelphia row home roof was historically devoid of edibles. In an effort to remedy this absurdity, my boyfriend and I climbed up to the roof yesterday to get our garden on. We began by discussing our expectations. Developing a strategy for infrequent watering was a top priority, as we’ll be away for portions of the summer and don’t want our precious veggies to shrivel in our absence. With no rooftop spigot, we contemplated capturing condensate from the roof’s AC units to pump through a drip irrigation system. We also considered bribing friends to hand water while we’re away. In the interest of cost and self-sufficiency, we ultimately decided that a successful garden would require self-watering planters.

We next discussed the practicalities of constructing our garden on a roof that we rent, rather than own. Waterproofing membrane protection was very important, as was avoiding rooftop staining that could result from soil-laden runoff streaming down the roof’s shiny new silver surface. Weight distribution was another consideration, so we considered the garden’s size and location. The planters should be wide rather than deep, to minimize weight, and large enough to support multiple crops at once. We decided to place them along the roof’s south parapet (knee wall at the edge of the roof) to take advantage of a structurally strong part of the roof flanked by a built-in wind break.

With a rough plan in mind, we headed to a few big box stores to see what creative materials we could find to build our planters, which we hoped would last for years to come. We searched and searched. Plastic storage bins at Ikea were likely not food-safe, wood containers at Lowe’s would not have held water, large planters were too heavy and contained drainage holes.

Self-watering planter with internal reservoir || photo by Lauren Mandel

But then, we found it: the Patio Pickers Planter. This 24″ x 20″ x 10″ plastic bin contains a water reservoir at the base, separated from the planting area by a plastic grate. Water enters the reservoir through a “fill tube” that extends from the surface of the planter into the reservoir. Excess water seeps out through overflow holes at the top of the reservoir to prevent the soil and roots from becoming overly saturated. The planter came with wheels that we chose not to attach; after all, we wouldn’t want our vegetables blowing across the roof! In its entirety the design is surprisingly similar to that pioneered by EarthBox in 1994.

Step 1 | Buy a self watering planter or acquire a large, food-safe plastic bin and a 2″-4″ thick plastic material to create the reservoir. An open-cell plant nursery tray or soda bottle tray turned upside-down would provide an inexpensive reservoir.

Cut landscape fabric to size || photo by Lauren Mandel

Step 2 | Cut a piece of landscape fabric at least 6″ larger than the planter’s top in all directions. For this planter I cut a 36″ x 32″ rectangle. The fabric itself should be thin and highly porous. We found an inexpensive fabric at Lowe’s made of recycled plastic bottles. Creating a fabric “tray” that fits inside the planter requires a series of cuts and folds, and maybe some Duck tape. First, slit the fabric roughly 6″ from one corner to create a rectangular flap. Pull the flap until it overlaps completely with the adjacent fabric and creates the first corner. Hold flap in place with Duct tape or anther tape that grips in water. Repeat for the remaining corners while pushing the fabric deeply into the corners to prevent air gaps. Alternate: fold inverted “hospital corners” instead of cutting and taping.

Next, cut a slit through the fabric to accommodate the fill tube. The design of this planter designates a specific corner, others may not.

Place wet soil in corner pockets || photo by Lauren Mandel

Step 3 | Some self-watering planters provide pockets for soil that reach down to the base of the reservoir. The soil in these locations is intended to wick water up to the surface soil when the reservoir is low. If your planter contains pockets, line them with landscape fabric if necessary. Fill the pockets with soil, then wet thoroughly and fit the fabric “tray” back in place.

Fill planter with garden soil || photo by Lauren Mandel

Step 4 | Fill the fabric “tray” with garden soil. Most off-the-shelf organic vegetable/herb blends are ideal in both composition and capillary potential (ability to wick water). We used one, 35 liter bag of soil per planter. Blend compost or other amendments into the soil as you please.

Plant veggie starts or seeds || photo by Lauren Mandel

Step 5 | Plant those veggie starts! You may alternatively decide to plant seeds, but keep in mind that starting seeds indoors is often more reliable and will allow you to keep more mature, productive crops on the roof. We planted beets, micro greens, two kale varieties, fennel, basil, chives, and head lettuce. We’ll plant heirloom tomatoes in an additional container once the starts are ready.

Optional: Before planting secure black plastic over the top of the planter to minimize surface evaporation and weed pressure. Cut slits in the plastic to accommodate veggie starts, then plant through the slits.

Fill reservoir with water || photo by Lauren Mandel

Step 6 | Fill reservoir with water using a pitcher, bucket, or hose (if you’re lucky enough to have a rooftop spigot!). This planter’s reservoir holds 2 gallons of water and will likely need to be filled once per week or twice during heat waves. We also surface watered to give the plants a boost, and will hand water every morning for the first week until the roots begin to reach the reservoir. If you installed black plastic over the soil be sure to water each veggie start through the slits in the plastic.

Level planters while distributing the load || photo by Lauren Mandel

Step 7 | If your planter has feet, place each pair of feet on a material that will distribute the load, such as a pressure treated pine 2″ x 4″. Shim the planter as necessary to ensure the reservoir water remains level.

Vuala! Your DIY self-watering planter is complete! Now you can put your energy into finding delicious summer recipes for your rooftop produce to share with your friends.

gaga for greenhouses!

Lucas Greenhouses || photo by Lauren Mandel

Confession: I’ve always been a soil lovin’ gal. I never gave much mind to high-yield greenhouses nor year-round production, but recently, I’ve turned positively gaga for greenhouses! I don’t know what’s come over me. Maybe it’s the glass house’s sleek architectural lines that draw me in. Perhaps the appeal lies in the mechanical precision applied to watering and ventilation, or heck, maybe high-tech greenhouse production simply fulfills my passion for efficiency.

Top to bottom: Golf cart transit, Colorful pansy beds, Mini plug for transplant || photos by Lauren Mandel

Last week Jeff Warschauer from Nexus Corporation – a leader in the greenhouse industry – toured me and my coworkers from Roofmeadow around 23 acres of commercial greenhouse space in Monroeville, NJ. The facility impressed the pants off of us. Lucas Greenhouses, established in 1979, is an award-winning family-owned plant nursery that sells to independently-owned garden centers and landscaping companies throughout the Mid-Atlantic. The company almost exclusively produces annuals, with an occasional herbaceous perennial and vegetable start in the mix.

Zipping from greenhouse to greenhouse on a near-silent golf cart I gasped with amazement as vibrant pansy beds flew by. The blur of color ended as Jeff pulled over to point out cutting-edge greenhouse features. A highly-calibrated computer system throughout the facility monitors and adjusts each greenhouse’s climatic conditions to meet the temperature and humidity needs of each individual greenhouse. Vents atop the peaked greenhouses open and close throughout the day to cool and dehumidify the growing environment while gradually hardening off the plants. During cool months, a sophisticated radiant heat system pumps hot water under the floor of several production houses. Others are heated by radiant “fins” (linear aluminum segments under radiant piping) suspended in the air. I was stunned by the sophistication and breadth of the operation.

What does a commercial, ground-level facility like Lucas Greenhouses have to do with rooftop agriculture? Everything. Jeff explained that many features we examined are directly transferable to rooftop greenhouses. Special considerations such as backup heating systems and selecting polycarbonate glazing rather than glass can make or break an rooftop greenhouse operation. Hydroponic systems that utilize harvested rainwater from the greenhouse roof can also be key for a commercial rooftop farm.

The level of innovation and dedication that Lucas Greenhouses owner George Lucas brings to the table is remarkable. His business remains competitive with the large, national suppliers, as evidenced by the company’s Greenhouse Grower Magazines “Grower of the Year” award in 2009 and 2012.

As we ruminate on our own rooftop farming projects, let’s remember to gain inspiration from a variety of sources – even those on the ground.

Lucan Greenhouses’ 100% open roof structures || photo by Lauren Mandel

top notch affordable housing

Arbor House greenhouse construction || photo by Jeff Warschauer

Watch out America, there’s a new breed of affordable housing in town. Nestled in the Morrisania neighborhood of the Bronx, the Arbor House is reshaping the way cities envision low-income housing projects. The eight story apartment building opened its doors to New York City’s low-income population in February 2013 with designers, developers and policy makers watching with anticipation. What’s so unique about this development? The LEED Platinum-certified building is topped with a 10,000 square foot (0.2 acre) hydroponic farm.

The 120,000 square foot building, designed by New York-based ABS Architects and developed by Blue Sea Development Co., includes 124 apartments designated for low-income households earning less than 60% of the area median income, or $49,800 for a family of four. Twenty-five percent of the units are reserved for New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) residents. Unlike the neighborhood’s sea of two-story public housing buildings built by NYCHA in the mid-1950s, Arbor House rises tall and contains building features generally associated with high-end development. In addition to the rooftop farm the building features a living wall, air filtration systems, local and recycled construction materials, low and zero VOC finishes, indoor and outdoor exercise areas, and art and music clad stairwells to promote walking. The building lies in one of New York City’s worst districts for asthma and obesity, so exercise and fresh food access were project priorities.

Rooftop greenhouse construction || photo by Jeff Warschauer

Arbor House’s hydroponic rooftop farm yields enough produce to feed 450 people per year. Chemical-free vegetables, herbs, and fruit are available to building residents and local community members year-round through Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) distribution. CSA members buy what’s called a “share” from the farm in exchange for a box of roof-fresh food each week. The remaining produce – around 40% – is distributed to the community through local outreach to schools, hospitals and markets. Vuala.

The building’s handsome, even-span greenhouse conforms to the roof’s geometry to maximize rooftop acreage. Colorado-based greenhouse industry leader Nexus Corporation designed and built the climate-controlled structure, which captures rainwater for use within the hydroponic system. Nexus is similarly responsible for Gotham Greens‘ rooftop facilities throughout New York City, and a slew of other fascinating rooftop projects – both agricultural and non-agricultural – around the country. The farm itself is operated by Sky Vegetables, a Boston-based urban farming company. In an NYCHA interview with Sky Vegetables President Robert Fireman, Fireman stated that, “Sky Vegetables is proud to partner with Blue Sea Development and city and state agencies to build one of the most forward and innovative projects in the nation.” He went on to say that the project will create “a national model for sustainable food production.”

Hydroponic greens || photo by Marcus Santos

In an era of corruption and questionably effective affordable housing precedents, how did this high-reaching vision actually materialize? Arbor House reached fruition thanks to a public-private partnership between NYCHA, the Department of Housing Preservation and Development and Blue Sea Development. The $37.7 million project is part of Mayor Bloomberg’s New Housing Marketplace Plan, a multibillion dollar initiative to finance 165,000 affordable housing units for half a million New Yorkers by the end of the 2014 fiscal year. As such, the development was eligible for and received significant savings through local, city, and state subsidies, Reso A funds, tax credit equities and tax exempt bonds. Blue Sea Development Co. saved additional money by purchasing the Arbor House lot from NYCHA at a below market rate.

Thanks to collaborative, cross-industry efforts, the Arbor House proves that fresh food access is finally within reach for some low-income New Yorkers. The project’s beaming success is sure to inspire future affordable housing developments and may prove to reshape our housing skyline.

feeding our city + our soul

Ledge Kitchen + Drinks || photo by Patrick Rogers Photography

Urban agriculture has crawled up walls and fire escapes onto rooftops across North America. As we cultivate our rapidly greening skyline, we’re hungry to learn the potential of the blossoming Rooftop Agriculture movement. On March 5th I had the privilege of speaking at the Philadelphia Flower Show – the world’s largest and longest-running flower show – about this very topic. Here’s an excerpt from the talk (not to be reproduced without permission):

We’ve all seen veggies growing in community gardens. Some of us may have seen edibles peaking out of window boxes, growing in the public-right of way (that strip between the sidewalk and the street), maybe in vacant lots, or even on rooftops. Rooftop agriculture has tremendous potential to feed our cities and our soul.

Right here in Philly, there are over 16,000 acres of rooftop [1]. If 0.5% of these roofs were converted to farms and veggie gardens, it would exceed the amount of area Philly currently has under production with all the urban farms and community gardens combined [2]. In 2008, Philly’s community gardens alone produced over 2 million lbs of summer vegetables [3]. Just think how much food we could grow right here across our skyline.

Ok, so I’m kind of nerdy, and I actually did the calculation. If 6.5% of Philly’s total roof area was converted to hydroponics (around 1,050 acres), we’d grow enough food to feed our 1.5 million residents. I’ll say that again. If 6.5% of our rooftops grew food hydroponically, we could provide every Philadelphian with fresh produce. Holy moly.

Lauren Mandel presenting at the Philadelphia Flower Show || photo by Anita Davidson

Now, I’m a green roof designer. Part of my job is taking idealistic scenarios and slapping on some pragmatism. The first thing to consider when talking about green-washing a city’s skyline is weight. Not every roof is strong enough to support a farm or garden. Each roof, in fact, is designed to support a specific amount of weight, or load… Most buildings are designed to meet the load requirements set forth by the local Building Code. Some buildings can hold more weight than expected because they were designed to support higher loads or they were built back when the requirements were more strict. Other buildings can support less weight than expected because they’ve become weaker over time. The bottom line is that each building can support a specific load. If you’re going to grow food up there, you need to know what that load is, and only a structural engineer can tell you.

The second pragmatic consideration is how, exactly, are all these people with strong roofs going to grow food up there? I mentioned hydroponics earlier but that’s just one way to skin the cat. Containers and raised beds are used most often on top of homes. They’re also used on top of apartment buildings, office buildings, churches, schools, community centers; anywhere where home or community gardening takes place. Farming (which I define as growing food for sale or direct use in the commercial building below like restaurant or hotel) often utilizes a different approach. Row farming and hydroponics are the most common rooftop farming strategies.

Each of these methods (container gardening, raised bed production, row farming, and hydroponics) has different costs, yields, and longevity. In general, container gardening is the least expensive and provides the lowest yields. Hydroponics requires the largest initial investment but provides the highest yields, and often highest profit margin. Each production method caters to a different user group and produces unique benefits.

Brooklyn Grange farmers’ market goods || photo by Jake Stein Greenberg

… Communities benefit from rooftop agriculture as they do with all other types of urban agriculture. Fresh food access is the first benefit that comes to mind… When food is grown locally, in an urban or peri-urban farm, fewer dollars are spent on transportation and fossil fuels. There’s less air pollution from this decreased transportation, and often times less packaging and food waste. Urban agriculture also fosters community building. Gardening with neighbors and friends in a community garden or neighboring properties is an incredible way to make friends, exchange knowledge, and share food. Urban agriculture also allows us to teach kids how to garden and appreciate healthy food choices. Sometimes they’re the ones teaching us. More formal educational opportunities are possible when classrooms are taken outside to learn in the garden.

The main community benefit that distinguishes rooftop agriculture from ground-level urban agriculture is that rooftop agriculture takes place in a safe, secure, convenient location. To give an example, Chicago’s South Side is a dangerous place. Urban gardens weren’t successful because kids didn’t feel safe outdoors. In 2006 the Gary Comer Youth Center opened its doors, with an 8,000 sf educational rooftop farm built for neighborhood youth to learn about gardening and healthy eating. For the first time these kids could play and learn outside in a safe, secure, convenient environment.

… The last thing I want to touch on is the urban food system. I mentioned feeding our city with hydroponics at the beginning of the talk. That’s because hydroponics offers the highest yields of any rooftop growing method. Rooftop farming companies like Gotham Greens, in Brooklyn and Queens, are run by savvy CEOs, with large staffs and multiple locations. Production relies upon high tech equipment that’s highly calibrated, with the ideal growing conditions provided for each type of crop. And boy do these hydroponic greenhouses grow a lot of food! In fact, Gotham Green’s rooftop greenhouses grow 20-30 times more food than ground-level farming, while using 20 times less water.

Sand Family with freshly-picked rooftop cucumber || photo by Lauren Mandel

… Hydroponics is an incredible form of agriculture, but by now you should understand the diverse value of all the different types of production. All types of rooftop agriculture are important. Collectively they address community and business needs, while keeping food miles to a minimum. While rooftop agriculture will continue to expand as people like you and me recognize its value, we must remember that rooftop agriculture works in concert with other types of urban agriculture to create the urban food system. The system is like a web.

Diversity in a food system equals resilience. So as our urban food system continues to diversify, it will get stronger and stronger. The backbone of this system, however, is rural agriculture. You didn’t think I’d say that, did you?! Well it’s true. Rural farms play a critical role in the national food system, so we must always acknowledge that urban agriculture will not replace rural agriculture. We’re simply diversifying the system.

So while you’re gardening your rooftop and indulging in its delicious rewards, remember that you’re garden is part of something much, much bigger.

———-

[1] Forsyth, Phil. “Up On the Roof: Expanding Urban Food Growing.” Permaculture Activist, no. 79 (2011).

[2] Kremer, P., DeLiberty, T. “Local Food Practices and Growing Potential: Mapping the Case of Philadelphia.” Journal of Applied Geography, 31:4 (2011): 1252-1261.

[3] Popp, Trey. “The Park of a Thousand Pieces.” The Pennsylvania Gazette, July/August (2011).

EAT UP

EAT UP