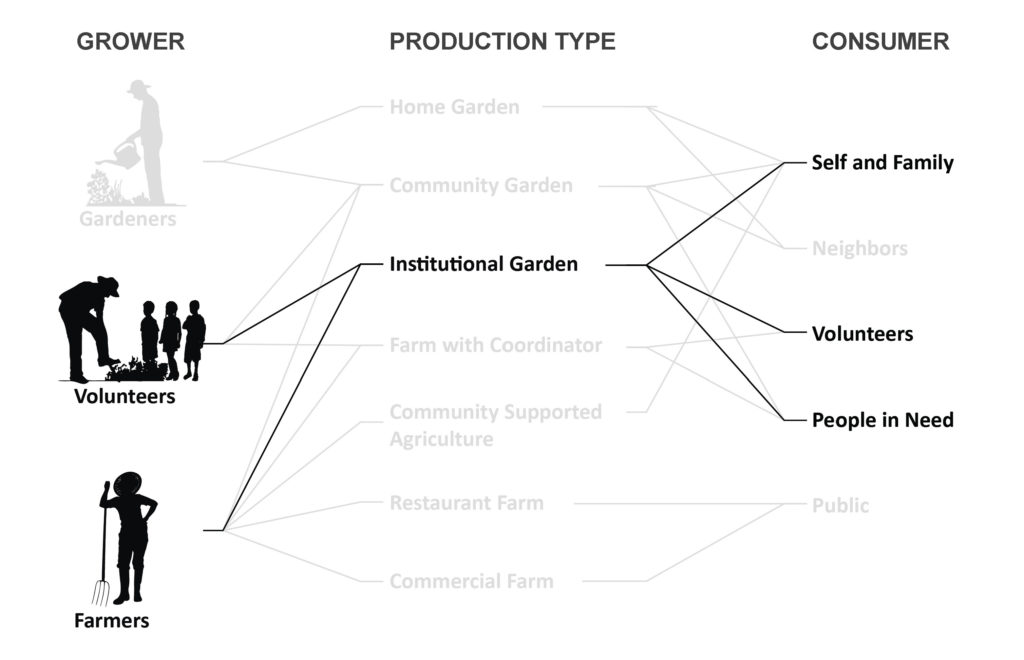

business model basics

As a landscape architect, I help clients achieve their vision for a development project’s outdoor space. The types of projects vary wildly–from schoolyards to federal buildings to university campuses–and many involve landscapes on structure. Increasingly, clients tell me that they envision these spaces as rooftop farms.

Once my initial excitement (and inevitable blushing) subsides, my response is usually, “Excellent! So who do you think will grow the food, and who will eat it?” You wouldn’t believe the number of times that clients respond, “Oh, I have no idea.” My job then quickly pivots toward helping them develop a business model.

The Swiss business theorist, Alexander Osterwalder, defines the term business model as that which, “describes the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value.” In the case of rooftop farms, value could be derived from many things, such as revenue generation, access to rare crop varieties, education, or helping people in need. Only when this orientation is established, can a rooftop farm can be designed to meet user needs.

Here are Alexander Osterwalder’s nine components to building a business model. This will help you tremendously when trying to establish a bulletproof business model for your own rooftop farm!

- Key partnerships

- Key activities

- Key resources

- Value proposition

- Customer relationships

- Channels

- Customer segments

- Cost structure

- Revenue streams

top 10 reasons to buy EAT UP this holiday season

Not sure what to give your hip, garden-loving, urban foodie this holiday season? How about a carbon-neutral gift that they’ll use to gain inspiration and change the world? “EAT UP | the inside scoop on rooftop agriculture” makes the perfect gift or stocking-stuffer for your mom/dad/aunt/uncle/cousin/daughter/son/friend/neighbor, or even that cute guy down the street. Through case studies, checklists, and interviews with rooftop agriculture’s industry leaders, this book inspires readers to garden their own rooftop and farm the skyline. Don’t fret, EAT UP‘s available through Amazon Prime and as an e-book.

In case you need some extra convincing, here are the top 10 reasons to buy EAT UP this holiday season:

amber waves of grain

Rooftop wheat field in Chicago || photo by Chris Murphy, Omni Ecosystems

In Chicago, green roof designer and Omni Ecosystems CEO, Molly Meyer, selected an unlikely plant species for atop Studio Gang’s office: hardy winter wheat. A wildflower meadow mix was originally slated for the 5,000-square-foot roof, but the project’s late-season seeding prompted the Indiana-native to add the quickly-establishing, edible species to increase the roof’s winter cover. Incidentally, the wheat grew so prolifically that Omni Ecosystem’s partner company, The Roof Crop, harvested the grain with the help of students from After School Matters. The 2016 harvest yielded 60 pounds of high-quality pastry flour, which was baked into chocolate chip cookies (yum!) by local bakery/cafe Baker Miller.

The project recently won a 2018 Honor Award from IL-ASLA in Landscape Architectural Research, which puts this rooftop wheat prairie back in the spotlight. I wanted to learn about the potential for skyline grain fields throughout the Midwest, so I asked Molly:

Harvesting the wheat with scissors || photo by Hannah Hoggatt Photography

[LM] When specifying hardy winter wheat for the Studio Gang roof as a winter cover crop, did you ever think a harvestable crop would result?

[MM] …To our knowledge, no one had attempted a green roof grain harvest, and in general, cereal crops are not included in urban agriculture operations and discourse. It was a fascinating opportunity. We worked with The Roof Crop to determine the logistics of collecting, processing and baking the grain into an edible product. We had conducted a toxicology test to confirm that the grain could be consumed; the tests were clear, and the grain yielded a high-quality pastry flour. We certainly did not predict that when we seeded the roof!

[LM] Have additional wheat crops been seeded and/or harvested since the first harvest, in 2016?

[MM] On Studio Gang’s roof, the design goal from the beginning had always been for the roof to support native plants in an ultra-lightweight system. The wheat field was a delightful phase during the ecological establishment and evolution of the rooftop’s ecosystem. Today the Studio Gang Architects roof supports native plants as originally intended. After a brief interlude as a wheat field producing cookies for humans, this rooftop wildflower meadow is still producing food- food for pollinators!

Baker Miller processing the wheat harvest || photo by Hannah Hoggatt Photography

[LM] Have you planted wheat on any other rooftops?

[MM] We still use winter wheat as a cover crop for many of our green roofs. None have matched Studio Gang in terms of grain production, but that is intentional. Studio Gang’s rooftop proved that wheat thrives in our system, and knowing that, we would seed a harvestable amount only if that is a specific goal for the project. Not everyone wants a wheat field; though, a couple breweries have gotten excited about the idea now that they know it is possible!

[LM] Is rooftop wheat production feasible at a commercial scale, say, 1-acre?

[MM] That’s a really exciting question. It is possible, but it’s also uncharted territory. An Omni Green Roof could certainly support a 1-acre wheat field, but new tools would make a larger harvest commercially viable. From cutting to threshing and winnowing to milling: wheat can be a labor-intensive crop to harvest and process. On Studio Gang, we hand harvested with scissors- less efficient than it could have been if we were not also trying to protect the establishing meadow in the understory. A few hours into the harvest, we joked about inventing a rooftop combine. It is funny to imagine, but in seriousness, it is the kind of innovation needed to scale rooftop wheat production.

[LM] Do you think this innovative approach to green roof plant selection could influence future rooftop farms in the Grain Belt and beyond?

[MM] There is a incredible interest in using wheat on other projects and more broadly in innovating on other projects like we did at Studio Gang. The wheat project was exciting because it challenges conceptions about urban agriculture. It was a great learning moment for Omni, The Roof Crop and for our industry. We showed that rooftop grain production is possible, and the positive response that followed our harvest and use of the crop captured imaginations and inspired more ideas. We are excited about what’s to come!

graze the roof

Figueras Polo Stables at El Yacaré || photo by Daniela Mc Adden

In La Pampa, Argentina, the Figueras Polo Club offers an unexpected form of rooftop agriculture: pastureland. The club’s 44-stall stables and surrounding polo grounds provide owner Ignacio Figueras — Argentinian polo star, celebrity horse breeder, and the face of Ralph Lauren Black Label — a swanky place to entertain potential buyers.

Wild, native grasses || photo by Daniela Mc Adden

“The roofs are planted with wild native grasses in an intentional contrast to the perfection of the polo field’s turf,” says project architect Juan Ignacio Ramos, founder of Buenos Aires and New York-based architecture firm Estudio Ramos.

Pastureland above the 44-stall stable || photo by Daniela Mc Adden

The roof’s biodiversity likely attracts grazing polo ponies by offering nutrients and seasonal flavors supplemental to those found in the surrounding turf grass. Like other green roofs on low-lying buildings, the pastureland may additionally ease temperature fluctuations within the 41,440 square foot facilities below.

The ground plain berms to the roof to provide access || photo by Daniela Mc Adden

Manicured landform connects the polo grounds to the rooftop pasture. “The slopes serve as both, access to the roof and as natural stands from which to observe the polo matches,” explains Ramos. Aesthetically and functionally, this unique destination remains strides ahead of the competition.

One of many polo ponies || photo by Daniela Mc Adden

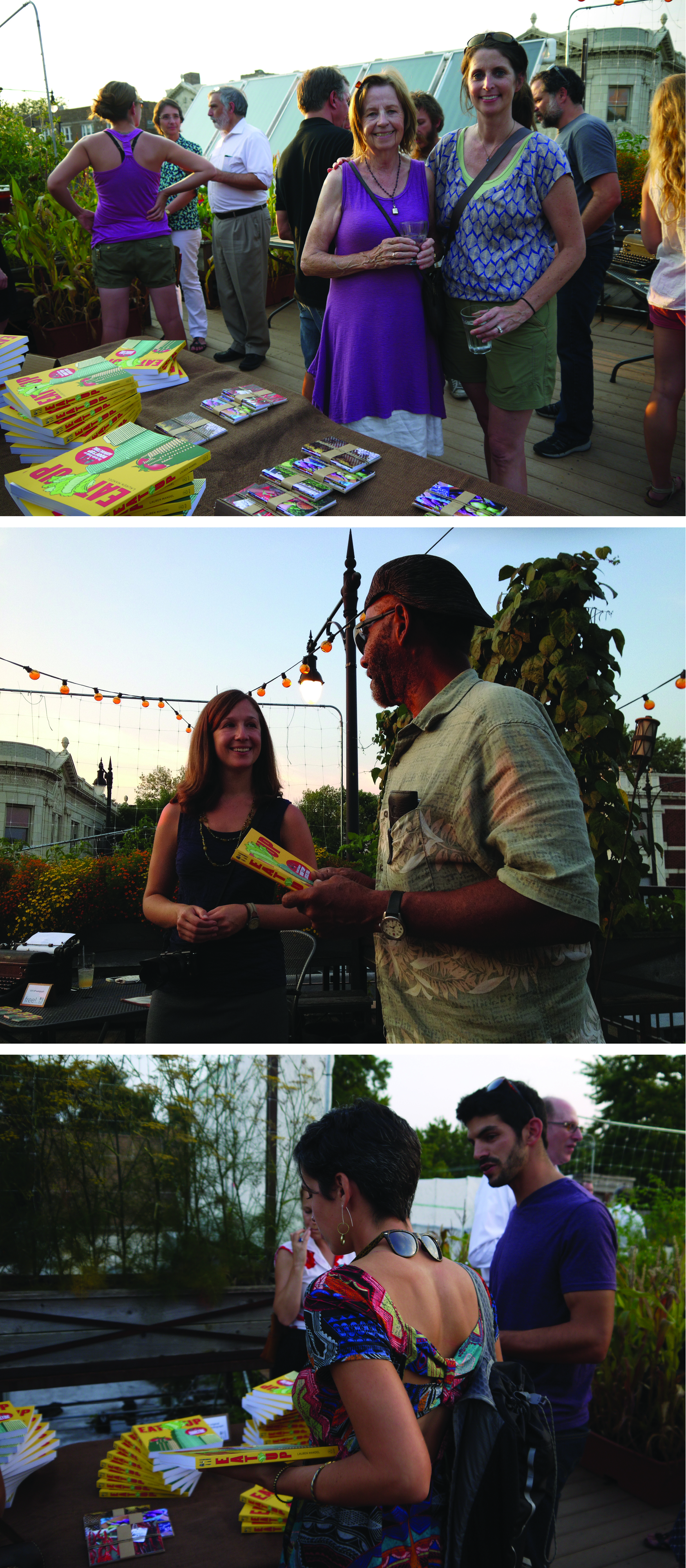

Whole Bazaar rooftop book sale

Roof-to-Table Launch Event Philadelphia || photo by Jane Winkel

Roof-to-Table Launch Event Chicago || photos by Paula Mandel

Despite this year’s erratic weather, spring has officially sprung! For gardeners and aspiring DIYers alike, this could mean that you’ve been quietly plotting your early season veggie planting, or maybe you’ve been dreaming of a brand new garden.

If you’re planning to grow this year’s edibles on a roof, balcony, or fire escape, you’ll likely have more than a few questions. Luckily, “EAT UP | the inside scoop on rooftop agriculture” (New Society Publishers, 2013) is here to help! As the first full-length book about rooftop food production, EAT UP delivers the answers you’ll need.

You can buy this carbon-neutral guide as a book or e-book through all the regular sellers (Amazon, Barnes & Noble, etc.). But if you’re in Philadelphia on April 8th, hang tight on that purchase! Come meet EAT UP author Lauren Mandel, PLA, ASLA on the roof of Whole Foods Market South Street and buy a fresh copy in person. You’ll have the chance to chat about your own rooftop garden, buy roof-to-table notecards and postcards, and can even get your book signed, if you’re so inclined.

We’ll see you on April 8th at the market’s Whole Bazaar event, rain or shine!

data we can eat

McCormick Place Rooftop Farm test plots || photo by Lauren Mandel

Edible crops are dappling our cities’ skylines in growing numbers, and yet, the blossoming North American rooftop agriculture movement remains in its infancy. As rooftop farmers and gardeners increasingly build knowledge by experimenting and improvising with things like crop selection, staking techniques, and soil amendments, is there room at the table for formal scientific inquiry?

Rooftop fennel || photo by Patrick Rogers Photography

In celebration of my one-year anniversary as a landscape performance researcher (and licensed landscape architect!) with the Philadelphia-based landscape architecture and ecological planning firm Andropogon, it seems appropriate to give a nod to research. Entering this world of site performance analysis has heightened my awareness of the need for field research, or in this case “roof research” (pun intended), to cultivate useful information for rooftop agriculture stakeholders, from growers to restauranteurs to entrepreneurs.

At its core, scientific inquiry allows us to better understand our world through developing questions and then proposing evidence-based explanations. This process may allow us to notice trends, such as tomato plants producing more fruit on rooftops than at-grade, or even formulate cause and effect theories, like increased soil drainage causes increased tomato fruit production. Building a body of scientific research around rooftop agriculture is essential in maximizing the legitimacy of our young movement and the quality/efficiency of production. While publications exist about the benefits of rooftop agriculture and opportunities for industry-wide growth, surprisingly few studies have been published that address the technical “how to” of rooftop farming or vegetable gardening.

One notable rooftop farm engaged in an experimental study in 2013. The McCormick Place Rooftop Farm launched a “thin farming” research effort to determine the optimal soil amendment regiment for a smattering of rooftop crops grown in full sun and partial shade. The study, conducted by the Chicago Botanic Garden’s urban agriculture education and jobs-training initiative, Windy City Harvest, involved 20 test plots that composed the then, 1/4-acre farm, with systematic additions of 0%, 30%, 50%, or 70% amendments (by volume) in the planting hole of each veggie start. Daily observational data fed into a study and informed the subsequent year’s crop management strategy. Since that time, the farm has expanded to 2.5-acres – the Midwest’s largest rooftop farm – and produces 8,000 lbs. of produce annually for use by the McCormick Place convention center in the building below.

How can you engage in scientific inquiry within your rooftop farm or veggie garden? Here are six easy steps to follow:

1| Research question: Develop a question that can be answered through the collection of quantifiable data, such as pounds of fruit, height of plants, frequency of irrigation, or number of maintenance visits. This question may be causal in nature: How does soil drainage affect tomato yields?

2| Literature review: Perform a survey of published literature to better understand what questions others have asked, how they’ve investigated those questions, and what findings they reached. Like most non-academics, I don’t have access to expensive journal databases, like EBSCOhost, so I usually begin surveying the literature through Google Scholar. When I find relevant publications, I add them to a running list of references using the Purdue Owl Writing Lab‘s user friendly APA formatting rules.

3| Hypothesis: Based on your literature review, develop an educated guess about what will happen in your experiment: If soil drainage increases, then tomato yields will increase. Also acknowledge the opposite, or null hypothesis, which you will later accept or reject: If soil drainage increases, then tomato yields will not increase.

4| Experimental design: Next, plan an experiment in which you can change one condition, or variable, at a time (such as degree of soil drainage) while keeping all other conditions constant. This is how you isolate the variable you’re examining to support causal findings. You’ll need a comparison that shares the constant conditions, which will serve as the experimental control. Be sure that your sample size (such as number of tomato plants) is large enough to reach statistically significant findings, which can become even more significant it the study is replicated.

5| Data collection + analysis: Now you’re ready to carry out the investigation that you designed. Set a schedule for collecting data then make sure that the data is obtained the same way, ideally by the same person, each time. After the experiment is complete, thoughtfully analyze the data to draw relationships between evidence and explanations.

6| Communication: Sharing what you learned is the most critical step of the scientific process, assuming you aim to advance the rooftop agriculture industry’s knowledge base! Scientific communication traditionally involves publishing a paper in a scientific journal or presenting your results at a conference during a talk or on a poster. As a practitioner-researcher, I additionally find great value in writing about studies in trade magazines and blogs, and speaking about them at all sorts of conferences and events. These outlets generally reach audiences beyond the scientific community, and in the case of rooftop agriculture, the practitioners may be your target.

more bees please

Rooftop beehive in north Philadelphia || photo by Lauren Mandel

Standing on the roof of SHARE Food Program in north Philadelphia, the audible hum of bee wing vibration is hypnotizing. Workers dart out of their hives to forage for pollen and nectar, others sluggishly return with caked pollen baskets, and those within the stacked wooden boxes flap incessantly to cool the hives for their queen. Up on a roof these canopy dwellers are right at home, and with so much activity buzzing around the hives, it’s hard to believe these bees, like their brethren throughout the country, have a slim chance of survival.

Since its importation to the U.S. in the mid-1600s, the European honey bee (Apis mellifera) has unequivocally shaped our food system, contributing more than $19.2 billion to the value of crop production within the U.S., according to a 2010 study by Cornell University researchers. While most agricultural crops are visited by a variety of pollinator insects, the American Beekeeping Federation notes that certain crops, like blueberries and cherries, are 90% dependent upon honey bees for pollination. Almonds possess the unique quality of being entirely dependent, requiring an annual importation of 1 million colonies, or 41% of all U.S. managed honey bee colonies, just to satisfy California’s crop.

Native Hunt’s bumble bee (Bombus huntii) visiting a sunflower || photo by Clay Bolt

Tragically (particularly for almond lovers), in 2006 the U.S. honey bee population began plummeting due to Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), a syndrome resulting in the exodus and death of drones from the hive, leaving the queen and immature bees marooned, to perish. The definitive cause of CCD has yet to be scientifically determined, but speculations include parasites, pathogens, pests, poor nutrition, sublethal exposure to pesticides, climate change, and low genetic diversity, or some combination thereof. What a buzz kill.

But there’s hope! Enter North America’s 4,000+ native bee species. Do these insects have what it takes to pollinate our farm fields, yards, stoops, window boxes, and edible skylines? “According to scientists, natives are more than up to the task of filling in for beleaguered honey bees,” writes National Wildlife senior editor Laura Tangley in her provocative article, “Being there for the bees.” This diverse, rarely-studied group of insects co-evolved with many of North America’s native flowering plants and are therefore critical to our ecosystems and food supply. “In the United States alone, native bees contribute at least $3 billion a year to the farm economy,” says Mace Vaughan, an expert quoted in Tangley’s article. Native bees are solely responsible for pollinating crops such as tomatoes and eggplant, and much more efficient than honey bees at pollinating many native crops, like pumpkins, watermelons, blueberries, and cranberries.

Diverse native bee varieties || image by Clay Bolt

Taxonomically, all bees belong to the sub-order Anthophila and one of six families: Andrenidae (mining bees), Apidae (cuckoo, carpenter, digger, bumble, honey bees), Colletidae (plasterer bees, masked or yellow-faced bees), Halictidae (sweat bees), Megachilidae (leaf-cutter bees, mason bees, allies), and Melittidae (melittid bees). Unlike the honey bee, most native North American bees are relatively solitary in nature; nest underground, in hollow stems, or in dead wood; and don’t make honey. Their biggest threats to survival include disease, habitat loss, pesticide exposure, climate change, and most recently, insecticide spraying intended to target Zika-carrying mosquitoes. Despite these pressures, it’s conceivable that native bees’ incredible genetic diversity provides an advantage over the honey bee in resisting CCD. With more research, increased education about the habits and importance of native bees, and a ban on insecticide spraying, pollinator populations will hopefully stabilize.

Here’s how your rooftop farm or vegetable garden can help native bees and our food system:

- Provide nesting sites | Build or buy in a native bee nest (they’re beautiful!) for installation in your farm or garden, or on a nearby roof area. If you see ground-nesting native bees in your media, try to stay out of their way so they can do their job.

- Plant native flowering plants | Make sure a variety of native plants on your roof are booming from early spring through late fall to provide native bees with a variety of pollen and nectar sources. Long-blooming herbs offer a great supplement to vegetable plants.

- Offer a water source | Bees get thirsty! Make sure to provide a rooftop watering source so your pollinators don’t wonder off.

- Eliminate chemical use | Keep your rooftop farm or garden chemical free by avoiding synthetic insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, and fertilizers.

- Tell your friends | Don’t be shy about proselytizing what you’ve learned about supporting native bees! Make sure prospective growers know that your farm or garden is the bees knees.

chocolate skyline

Cacao “beans” drying on a rooftop in Ghana || photo by Toby Webb

This Valentine’s Day season I’d like to be as close to chocolate as possible, and consumer market trends suggest that I’m not alone. For those of us living far from the equator, though, the main ingredient in chocolate, cacao, travels an incredible distance to reach our plates. Cacao are seeds, often referred to as “beans,” found within football-shaped pods that grow from the trunk and branches of the cacao tree (Theobroma cacao). The tree is native to the South American lowlands and is now propagated within rainforests throughout the equatorial tropics and sub-tropics of Central America and parts of South America, Africa, and Asia.

Agricultural rooftop use in Granada (top) + Mexican farmers drying cacao out of their chickens’ reach (bottom) || photos by The Grenada Chocolate Company + Madre Chocolate/David Elliott

The process of deriving coco from the cacao bean is labor-intensive and is often performed by growers and plantation owners in remote areas. Once cacao pods ripen, they’re cut from the tree and the beans are extracted. The beans are fermented, laid on a flat surface to dry, and then generally exported to another country where they are roasted. The roasted beans are ground to a fine powder called cocoa, which is then blended with sugar and other ingredients to produce the creamy sweetness that we’ve grown to love.

“Cacao seeds, or ‘beans,’ have to be dried after fermentation as a measure to prevent molds [and] mildews from growing on them during transport,” explains botanical scientist and cacao expert Dr. Cindy Skema. “It is a bit of an art, though, because the beans must not be over-dried because they can become too brittle and that creates problems in processing.” As you may imagine, naturally flat areas for drying cacao beans are a rarity for many rainforest inhabitants. Some growers and plantation owners build structures specifically designed to dry the beans, with protective covers that are either static or slide on tracks, like a convertible roof, to protect the crop from incoming rain storms and shield the beans from insects and birds. Others lay beans on their village’s concrete, central square, as I’ve seen myself in rural Venezuela.

In isolated instances around the world growers have been seen industriously using their rooftops as drying grounds for cacao beans. Multiple examples exist in Trinidad, but growers and plantation owners in Brazil, Ghana, the Dominican Republic, Grenada (in the Caribbean), Vanuatu (in the South Pacific), and Mexico have also pursued the practice. In Oaxaca, Mexico, chocolatier consultant and author Clay Gordon visited a family farm that allocated roof areas to drying cacao because this location was, “out of the reach of chickens,” he says. Gordon explains, though, that drying cacao on roofs is not a common practice due primarily to, “the labor of getting the beans up there in the first place. Furthermore, not all roofs [in cacao-growing locations] are flat or sturdy – many of them are pitched and made of galvanized corrugated metal, which is not a good surface for drying beans.”

Cacao drying on rooftops in Vanuatu (top) + Trinidad (bottom) || photos by Zaia Kendall + Leonie Milner

Skema agrees that drying cacao on rooftops is not very common, but to her, the practice comes as no surprise. “It makes sense,” she says, “I mean [the roof] is a typically open, available space that gets very hot and is a bit cleaner than ground level, or at least without people [or] animals walking through.” Skema notes that around the world roofs are used to dry a variety of things, like edible plant material, meat, and clothes.

Agriculture involves not just food production, but also processing, or the preparation of crops for sale via washing, fermenting, drying, etc. Rooftop agriculture generally evokes images of crops strictly in production, even for me, and we rarely stop to think about supplementary agricultural practices fit for rooftops. Using roofs to dry cacao is a beautiful example of the creativity of farmers who, in all reaches of the world, have independently developed the same practice.

This Valentine’s Day, when you’re craving chocolate, pause to think about whether your indulgence spent part of its lifetime on a roof, under the sun, and what other non-production agricultural practices could occupy our rooftops.

—

Sources

Bletter, Nat. Email correspondance. 17 November 2015.

Gordon, Clay. Email correspondence. 18 November 2015.

Gordon, Clay. “Madre Chocolate-From The Road In Xoconusco, Chiapas.” Discover Chocolate, 7 March 2011. Web. 11 October 2015.

Skema, Cynthia. Email correspondance. 10 November 2015.

Skema, Cynthia. “Ka-Pow Cacao.” Morris Arboretum of the University of Pennsylvania. 100 E Northwestern Ave, Philadelphia, PA 19118. Lecture.

EAT UP

EAT UP